OSLO 2011: In-between Destiny’s Child and Rosemary’s Baby

During the last fifteen years the European architects’ have had an intense love relationship with the contemporary city. They have been trotting the globe for the places where the contemporary city, what ever it would be, would unveil itself as naked as virgin-like, but above all as meaningful as a revelation capable of reinventing the architecture itself. The architects have been competing in the Indiana Jones style, who would find the most contemporary city with the most exotic (and therefore the most real) conditions for the architecture production. This exoticness has been mostly measured in the terms of architecture’s size and the fastness of its construction. Usually, the new Babylon has been found in the places of the crouching tiger economies, somewhere in the countries of the rising sun. The European architects have seen the future in these places, but actually that was just a dream mirrored back from the stories that their grandfather architects had told them, stories about the brave builders of the rising European continent. Today, in the architects’ eyes, their European cities have stopped developing as the cities’ final chapter has been written somewhere in the European suburban hinterland. In Oslo things are bit different. The urbanization has taken over as much in the periphery as in the city itself. The following story is an urbanistic drama told in four chapters where the protagonists are real Oslo-projects placed in between the enthusiasm of a crouching tiger and the agonies of an old continent.

Episode 1: A Prophecy

In the early 1960’s the modernist architect Håkon Mjelva proposed a design for the down-town area of Oslo. The proposal was published in the national architecture magazine Byggekunst in 1964, along with his article “Can Oslo become a metropolis?” Mjelva discussed the necessity to strengthen Oslo as the cultural and business center of Norway, and described his proposal as a reaction against the decentralization policies through which many of the cultural, educational and state institutions were to be displaced at the peripheral parts of the country. Mjelva’s mega-proposal was structured around three main ideas: the introduction of the elevated pedestrian level which pragmatically expanded above the city’s infrastructure on the height of plus nine meters, the slim high-rise blocks placed in the north-south direction optimized to filter the view from the city towards the fjord and the opera house integrated with pedestrian level placed on the inner shores of the Bjørvika bay. The proposal was in accordance with the architecture culture’s spirit of the time – being a cocktail of CIAM and TEAM X ideas. Above all, it was a prophecy – an image capable of conjuring both Oslo’s emerging nightmares and its sweetest dreams.

Episode 2: The Arrival of the Future

In the 1980’s the financial capital started returning to the city after a decade long investment pause during which the Norwegian capital was exclusively injected into the emerging off-shore oil industry. Oslo was finally awakening. At the location where one of the city’s largest shopping malls was planned in the late 1960’s and aborted in the 1970’s, Vaterland area, a new development took place – the establishment of the infrastructural mixed use hub consisting of the main bus terminal, major indoor sports arena, hotel, shopping, offices, and a mosque. The competition was launched in 1982 and would be won by the collaborative of young architects, with the name LPO. Their proposal, OSLO M (M could stand as much for the meeting place as for the metropolis), was structured around the idea of a 400-meter-long building wall punctuated by the highway ramps, with the street level given to the bus terminal. The proposal would be completed by the late 1980’s, being strongly modified through the developer’s density matrices. The result was a structure with a 400-meter-long glassed-in street elevated above the city’s infrastructure, Oslo’s generic city on its own, unavoidably following some of the principles suggested twenty five years earlier. From its inception, the project would prime the position of being Oslo’s most hated, not because of its lacking architecture ambitions and craftsmanship, but because of the emerging need by the general (and architecture) public for something spectacular and iconic – the Oslo mood was in the making.

Episode 3: The Birth of the Model

Parallel to the arrival of the future at Vaterland, the west side started getting its own crown joules: the urban redevelopment of the waterfront at the former blue-collar bastion of Aker Shipyards. The building of Aker Brygge, the new city within the city, the first of its kind in Norway, was done in two stages: the first stage by Fredrik Torp and the second stage by Niels Torp, both members of the Norwegian architecture royalty. This was one of the first large-scale projects invested and built solely by the private capital. The architects had to reinvent their attitude (and knowledge) towards the development of the city and to their clients: how could an ambitious business idea be embedded into an urban development model? The answer was sought on the other side of the Atlantic; the Baltimore model seemed most applicable, while the architectural result was very much of that seen at London’s Docklands. The stakes around this project were high: the plans were presented to the politicians after the construction of the first buildings had started. Aker Brygge had constituted a model both an urbanistic one and a business one - one which would be exported to other Norwegian coastal cities and through which the Oslo architects would gain the self-confidence in relation to the city and its complexities, but above all to the rules of the large-scale private capital.

Post Scriptum

Is Oslo an exotic city? The question remains unresolved. The architects, who build it, love it; the architects who don’t build it, mistrust it. Whom to believe? Still the new city is emerging, as much along the fjord as of the fjord. The city where the economy has replaced the politics. Another city for another generation for another time. What else to say then: "This is no dream — this is really happening!" – the words explicated by Rosemary Woodhouse after she was impregnated by a demonic presence in Polanski’s movie “Rosemary’s baby”.

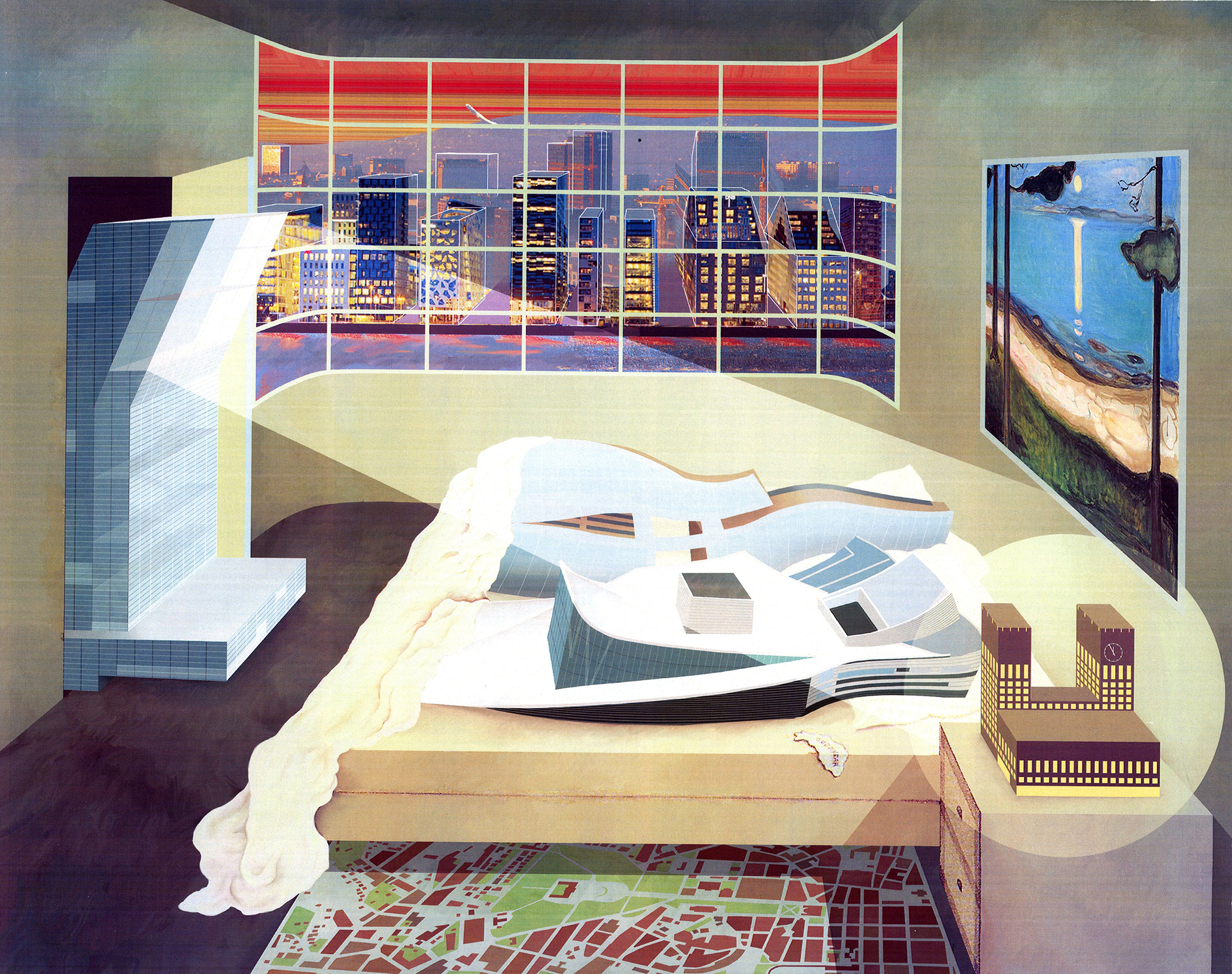

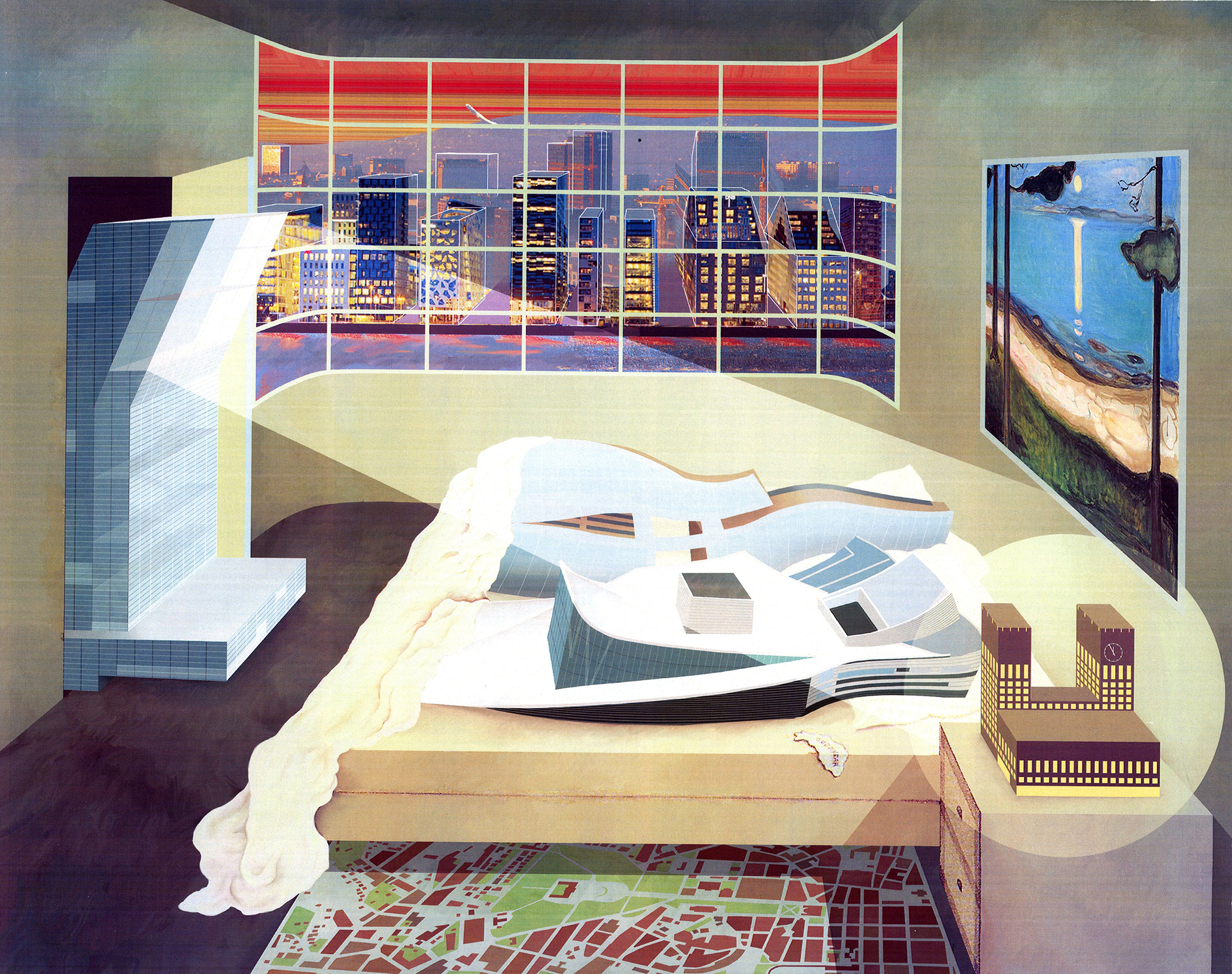

IMAGE: Urbanistic nachspiel in Oslo, featuring a Spaniard, an Italian and a Norwegian. Remake of Madelon Vriesendorp’s ‘Flagrant délit’ by MALARCHITECTURE.